Learning Question 3

1 Are enabling conditions in place to support a sustainable enterprise?

2 Does the enterprise lead to benefits for stakeholders?

3 Do the benefits realized by stakeholders lead to positive changes in attitudes and behaviors?

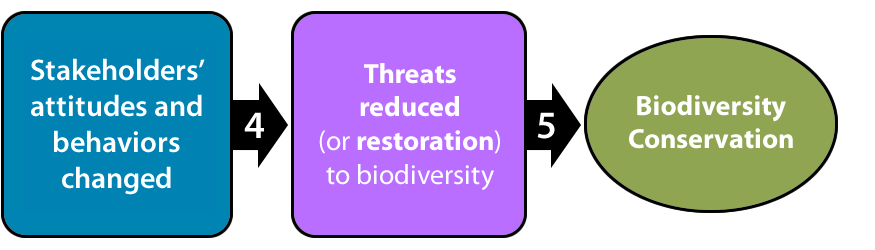

5 Does a reduction in threats (or restoration) lead to conservation?

Do the benefits realized by stakeholders lead to positive changes in attitudes and behaviors?

A key assumption of enterprise approaches to conservation is that stakeholders perceive that the benefits, most often income, of the new or modified activity outweigh those of continuing the unsustainable use of resources that are the focus of conservation.

Note: Superscript numbers indicate references at the bottom of each page, where links to many of these documents can be found. We are still in the process of uploading references to the documents page. Please contact us if you’d like a copy of a reference that hasn't yet been posted.

Note: Italicized text denotes findings discussed during events such as webinars and conferences.

Findings:

- Relatively small amounts of funds, equitably and transparently distributed can be persuasive for participants to change their behavior.10

- The enterprise must show some benefits (not necessarily income) in the first years in order to motivate changes in behavior.13,14

- The Biodiversity Conservation Network's (BCN) intent was to support enterprises that were linked to biodiversity (see Box 4 for a description of BCN’s hypothesis regarding linked enterprises). These results imply that, although cash income may not be important in influencing participants’ willingness to counter threats, participants do need some incentives to take action.13

- There was little evidence to suggest that individual cash benefits to participants lead to threat reduction.

- There was no association between the income contribution of the enterprise to total income of the average household and threat reduction.

- Contrary to expectations, conservation occurred regardless of the percentage of participant households receiving income from the enterprise.

- Qualitative results indicated that all sites with significant conservation outcomes had substantial noncash benefits.

- Noncash benefits, such as enhanced community confidence, were an important enabling condition for conservation outcomes and seemed to engender trust and cooperation between key participants and project staff. 2,13

- Project managers or governing authorities may need to impose limits on resource use9,15 so that enterprises do not become additional activities for participants, rather than a substitute for threat-inducting activities.6,15

- Forests, wildlife, and fisheries that are of interest to conservation are often a minor portion of the livelihoods of the rural poor; enterprises are often an additional source of income that usually do not replace their primary livelihood, such as agriculture.2,7

- Short project timeframes leave managers with uncertainty about whether the benefits from enterprises will be sufficient to motivate and enable participants to change behavior.3,5,12,15

- If benefits take a significant amount of time to be secured, it may be necessary to have a mechanism in place to provide stakeholders with shorter-term benefits in order to keep them engaged. (https://www.seed.uno/publications/longitudinal-research/88.html)

- It may be important to understand how benefits to participants might affect the behavior of those in the community that are not receiving benefits from the enterprise.8,10

-

In Uganda, the success of the enterprise was linked to community members willingness to sign an agreement with the protected area authorities. Communities agreed to change specific behaviors such as ceasing poaching activities, using alternative methods to reduce conflict with wildlife (elephants and chimps), and raising awareness and reporting others involved in illegal and unsustainable activities.20

-

In Mexico, a key issue with a butterfly handicraft project was failure to identify any market for the handicraft products. Participants become upset that they didn’t receive promised benefits which led to negative attitudes towards conservation and suspicion toward foreign conservation efforts.19

-

Behavior change appeared to be dependent on the amount earned from butterfly farming in Tanzania. More income seemed to lead to more participation in conservation. Land ownership was also key. With the benefit of land ownership allowed people to risk putting effort into the butterfly farming enterprise.19

- Receiving monetary benefits from a conservation enterprise can be associated with positive changes in behavior but there we start seeing that there was support for that assumption only about half the time [of the enterprises studied by Roe et al.]. There are other factors that are context dependent that influence that association.17

There are still important information gaps regarding the linkages between the enterprise benefits and attitude and behavior change, such as if and how engagement in the enterprise may change participants’ attitudes so that they change their conservation behavior. Measuring if and how the benefits (both income on noncash benefits) are leading to attitude and behavior change of participants is key to understanding the effectiveness of the conservation enterprise.

Documents Referenced

- Anderson, Jon, Mike Colby, Mike McGahuey, and Shreya Mehta. Nature, Wealth, Power 2.0: Leveraging Natural and Social Capital for Resilient Development. USAID/E3/Land Tenure and Resource Management Office. 2013.

- Anderson, Jon and Shreya Mehta. A Global Assessment of Community Based Natural Resources Management: Addressing the Critical Challenges of the Rural Sector. Washington D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. 2013.

- Andersson, Meike, Sara Scherr, Seth Shames, Lucy Aliguma, Adriana Arcos, Byamukama Biryahwaho, Sandra Bolaños, James Cock, German Escobar, José Antonio Gómez, Florence Nagawa, Thomas Oberthür , Leif Pederson, and Alastair Taylor. Case Studies: Bundling Agricultural Products with Ecosystem Services. Ecoagriculture Partners. 2010.

- App, Brian, Alfons Mosimane, Tim Resch, and Doreen Robinson. USAID Support to the Community-Based Natural Resource Management Program in Namibia: LIFE Program Review. Washington D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. 2008.

- Boshoven, Judy, Benjamin Hodgdon, and Olaf Zerbock. Measuring Impact: Lessons Learned from the Forest, Climate, and Communities Alliance. Washington D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. 2015.

- Boudreaux, Karol. Community-Based Natural Resources Management and Poverty Alleviation in Namibia: A Case Study. Mercatus Center, George Mason University. 2007.

- Clements, Tom, Ashish John, Karen Nielsen, Chea Vicheka, Ear Sokha, and Meas Piseth. Case Study: Tmatboey Community-based Ecotourism Project, Cambodia. Ministry of Environment, Cambodia and WCS Cambodia Program. 2008.

- Hecht, Joy and Arthur Mitchell. Global Sustainable Tourism Alliance (GSTA) Performance Evaluation. Washington D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. 2014.

- Koontz, Ann. The Conservation Marketing Equation: A Manual for Conservation and Development Professionals. Washington D.C.: EnterpriseWorks/VITA. 2008.

- Lessons on Community Enterprise Interventions for Landscape/Seascape Level Conservation: Seven Case Studies from the Global Conservation Program. Washington D.C.: EnterpriseWorks/VITA. 2009.

- Patel, Hetu, Sara Nelson, Jesus Palacios, Alison Zander, and Helen Crowley. Case Study: Elephant Pepper: Establishing Conservation-Focused Business. Bronx, NY: Wildlife Conservation Society. 2009.

- Pielemeir, John and Matthew Erdman. Performance Evaluation of Sustainable Conservation Approaches in Priority Ecosystems Project. 2015. (forthcoming)

- Salafsky, Nick, Bernd Cordes, John Parks, and Cheryl Hochman. Evaluating linkages between business, the environment, and local communities: final analytical results from the Biodiversity Conservation Network. Washington D.C.: Biodiversity Support Program. 1999.

- Torell, Elin and James Tobey. Enterprise Strategies for Coastal and Marine Conservation: A Review of Best Practices and Lessons Learned. Narragansett, Rhode Island: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island. 2012.

- Wicander, Sylvia and Lauren Coad. Learning our Lessons: A Review of Alternative Livelihood Projects in Central Africa, IUCN and ECI, University of Oxford. 2014.

- Martinez-Reyes, Jose E. Beyond Nature Appropriation: Towards Post-Development Conservation in the Maya Forest. Conservation and Society 12 (2). 2014.

- Hill, Megan, Natalie Dubois, Shawn Peabody. Conservation Enterprises: Exploring their Effectiveness [Webinar]. USAID Conservation Enterprise Learning Group Webinar Series. 2016.

- Environment Officers’ Conference Session Summary: Launching a Cross-Mission Learning Agenda on Conservation Enterprises. 2016.

- Booker, Francesca, Dilys Roe, Megan Hill. A Conversation with Dilys Roe and Francesca Booker [Webinar]. USAID Conservation Enterprise Learning Group Webinar Series. 2016.

- Senkungu, Robert, Judy Boshoven, Ashleigh Baker. Setting up for Success: Enabling Conditions for Conservation Enterprises [Webinar]. USAID Conservation Enterprise Learning Group Webinar Series. 2016.

- Russell, Diane, Judy Boshoven. Conservation Enterprises: Using a Theory of Change Approach to Synthesize Lessons on the Effectiveness of Interventions [Webinar]. USAID Conservation Enterprise Learning Group Webinar Series. 2014.

Learning Activities: Missions will share their experience and learn about best practices in building the enabling conditions for establishing a successful and sustainable enterprise. We propose to support this activity through a review and synthesis of existing publications on best practices for each of the enabling conditions of most interest to Missions and their implementing partners. The findings from the review will also be the topic for a discussion with the Learning Group. Missions may share their experience through the online platform, webinar presentations, and through facilitated email discussions.